How Peppermint Candy Caused One of Britain’s Deadliest Mass Poisonings

Five-year-old Orlando Boran was already dying when the doctor arrived. On Halloween afternoon in 1858, his family in Bradford was suddenly taken ill. Parents Mark and Maria, along with the tenants, were weak from vomiting and stomach pain. But Orlando and his two-year-old brother, John Henry, were seriously ill.

Dr. John Henry Bell was called to the residence where He found Orlando “He was completely pulseless, his face was pale, his lips were white and angry, and his eyes were sunken and half closed.” The doctor told the stunned parents there was nothing he could do. Orlando died within 15 minutes of the doctor’s arrival. John Henry followed soon after.

Bad crap

There was one thing every family member had in common: they ate Peppermint bullshita popular sweet, which Mark had bought the night before at the Green Market in Bradford. From the family’s symptoms, Dr. Bell quickly determined that they had been poisoned. He tested for one error using a Rheinsch test, in which he heated the sample with copper strips. The dark coating on which he formed confirmed his suspicions: the candy contained “a very large amount of arsenic.”

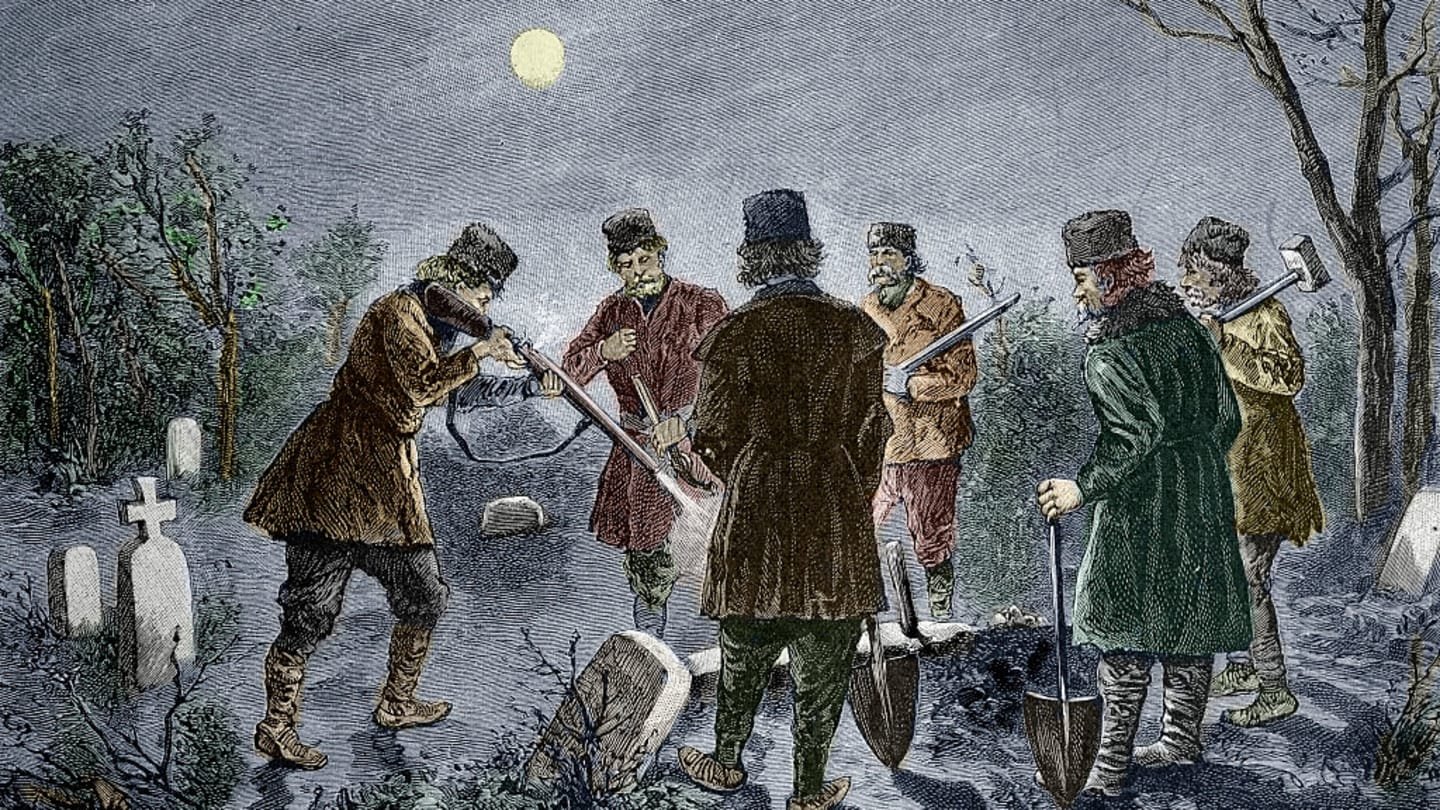

The police visited William “Humbug Billy” Hardacre, the owner of a market stall selling poisonous candy. But Hardacre himself was home sick, having sampled his deadly wares. The path led to wholesale confectioner Joseph Neal. He revealed that his workers made the candy following a common but dangerous practice: to cut costs, he replaced expensive sugar with “silly” (also known as plaster of Paris).

The fatal mistake occurred at Hodgson’s pharmacy, where the inexperienced assistant William Goddard had worked for less than three weeks. When Neal’s employee asked for the ridiculous substance, Goddard mistakenly took 12 pounds of powder from an unmarked barrel. Contains arsenic.

When Candy is killed

Mixing this arsenic with sugar and peppermint oil produced 40 pounds of deadly candy that was delivered to Hardacre on October 30. Neil and Hardaker both noticed that these insects were darker than usual, but did not pay much attention to them. Instead of getting the candy back, Neil offered it to Hardacre for a modest discount. That day, five pounds of fudge were sold from the market, enough to kill hundreds of people.

Police Chief Liverat spread word of the poisonous candy as quickly as possible. Town criers woke residents sleeping throughout the night. Police officers spread the word through their beats. By morning, warnings covered every wall within five miles of the city. But for many families, it was too late.

Several people have already died, and local doctors report treating 20 to 30 patients each. The poison was so strong that Liverat felt a “dizzy sensation” and experienced irritation in his nose and hands just handling the evidence. In court, analytical chemist Felix Remington testified that each bullshit contained about nine and a half grains of arsenic. Half of this amount was enough to kill an adult.

You may also like…

Add the mental thread as Favorite news source!

A lasting legacy

The final toll was devastating: 18 confirmed deaths, including 11 children (one as young as 17 months old). An estimated 193 people fell ill, although the real number was likely much higher.

pharmaceutical Charles HodgsonConfectioner Joseph Neal and his assistant William Goddard were both later charged with manslaughter He was acquitted. Hardacre was not charged, because he was also poisoned by the candy. This case highlights the serious lack of safeguards regarding the sale of poisons rather than deliberate criminal intent.

This tragedy became an incentive for reform. After a decade, Pharmacy Act 1868 It required that all poison sales be registered by qualified chemists, and that each toxin be clearly labeled – a hard-won protection sparked by Bradford’s planned shenanigans.

Post Comment